Even though I live not far from the old Nellie Bly Amusement Park in Brooklyn, for the longest time I had only the vaguest idea of who the real-life Nellie Bly actually was. I knew that she had been a newspaper reporter in the nineteenth century, but I had no idea just how remarkable a person she was – at least not until I happened across a brief mention of a record-setting race that she undertook around the world.

I was taken aback by the thought that in the year 1889 a young woman (she was twenty-five years old), unaccompanied and carrying only a single bag, would be daring enough to race around the world – and do it faster than anyone ever had before her. When I delved more deeply into the story I was even more amazed to discover that Nellie Bly was racing not only against time, but also against another young female journalist, Elizabeth Bisland, who set out from New York on the very same day, going in the opposite direction. I was captivated by the notion of these two woman racing each other around the world on trains and steamships, one traveling east, the other west.

As a writer, as well, I was thrilled by the prospect of bringing to life all of these exotic, fascinating places in the years 1889 and 1890. Though I was writing a work of history – every bit of this book is true – I wanted it to have all the suspense, the immediacy, the emotional impact of a novel. In writing it I tried to bring the journey vividly alive on the page: letting the reader travel behind the stone walls of the Amiens estate where Nellie Bly meets Jules Verne; through the foggy early-morning streets of London; along a moonlit Suez Canal; on a risky night-time ski trek across Sierra Nevada mountains blockaded by snow drifts twenty feet high.

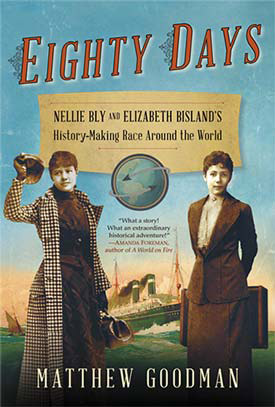

My interest in the story only grew when it became clear to me how different from each other Nellie Bly and Elizabeth Bisland were. Bly was a scrappy, ambitious newspaperwoman who sought out the most sensational stories; Bisland was a genteel poet and essayist who dismissed most newspaper writing as “a caricature of life.” Bisland hosted tea parties in her apartment for New York’s literary set; Bly was a habitué of O’Rourke’s saloon on the Bowery. The race around the world was Nellie Bly’s own idea, and she long fought to convince her editors to let her go; Bisland, on the other hand, undertook the trip only with the most extreme reluctance.

Yet as it turned out, both women proved to be extremely worthy competitors in their great race. I loved writing Eighty Days, and now that it’s completed, I’m thrilled by the prospect of introducing today’s readers to these two daring, courageous women from years past.