November 14, 1889

Hoboken, New Jersey

She was a young woman in a plaid coat and cap, neither tall nor short, dark nor fair, not quite pretty enough to turn a head: the sort of woman who could, if necessary, lose herself in a crowd. Even in the chill early-morning hours, the deck of the ferry from New York to Hoboken was packed tight with passengers. The Hudson River—or the North River, as it was still called then, the name a vestige of the Dutch era—was as busy as any of the city’s avenues, and the ferry carefully navigated its way through the water traffic, past the brightly painted canal boats and the workaday tugs, the flat-bottomed steam barges full of Pennsylvania coal, three-masted schooners with holds laden with tobacco and indigo and bananas and cotton, hides from Argentina and tea from Japan, with everything, it seemed, that the world had to offer. The young woman struggled to contain her nervousness as the ferry drew ever closer to the warehouses and depots of Hoboken, where the Hamburg-American steamship Augusta Victoria already waited in her berth. Seagulls circled above the shoreline, sizing up the larger ships they would follow across the sea. In the distance, the massed stone spires of

New York rose like cliffs from the water.

For much of the fall of 1889 New York had endured a near-constant rain, endless days of low skies and meager gray light. It was the sort of weather, people said, good only for the blues and the rheumatism; one of the papers had recently suggested that if the rain kept up, the city would be compelled to establish a steamboat service up Broadway. This morning, though, had broken cold but fair, surely a favorable omen for anyone about to go to sea. The prospect of an ocean crossing was always an exciting one, but bad weather meant rough sailing, and also brought with it the disquieting awareness of danger. Icebergs broke off from Greenland glaciers and drifted dumbly around the North Atlantic, immense craft sailing without warning lights or whistles and never swerving to avoid a collision; hurricanes appeared out of nowhere; fires could break out from any of a hundred causes. Some ships simply disappeared, like Marley’s ghost, into a fog, never to be heard from again. The Augusta Victoria herself was lauded in the press as “practically unsinkable”—the sort of carefully measured accolade that might well have alarmed even as it meant to reassure. A twin-screw steamer of the most modern design, only six months earlier the Augusta Victoria had broken the record for the fastest maiden voyage, crossing the Atlantic from Southampton to New York in just seven days, twelve hours, and thirty minutes. Arriving in New York, she was greeted by a crowd of more than thirty thousand (“The Germans,” The New York Times took care to note, “largely predominated”), who swarmed aboard to get a closer look at the floating palace, taking in her chandeliers and silk tapestries, the grand piano in the music room, the lavender-tinted ladies’ room, the men’s smoking room swathed in green morocco. Transatlantic travel had come a very long way in the half century since Charles Dickens sailed to America, when he eyed the narrow dimensions and melancholy appointments of his ship’s main saloon and compared it to a gigantic hearse with windows.

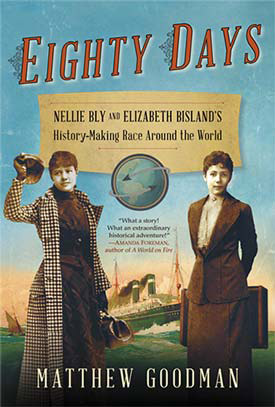

Dockside, the minutes before the departure of an oceangoing liner always had something of a carnival air. Most of the men were dressed in dark topcoats and silk hats; the women wore outfits made complicated by bustles and ruching. On the edges of the crowd, peddlers hawked goods that passengers might have neglected to pack; sweating, bare-armed stevedores performed their ballet of hoisting and loading around the ropes and barrels that cluttered the pier. The rumble of carts on cobblestones blended with a general hubbub of conversation, the sound, like thunder, seeming to come at once from everywhere and nowhere. Somewhere inside the milling crowd stood the young woman in the plaid coat. She had been born Elizabeth Jane Cochran—as an adolescent she would add an e to the end of her surname, the silent extra letter providing, she must have felt, a pleasing note of sophistication—though she was known to her family and her old friends not as Elizabeth or as Jane but as “Pink.” To many of New York’s newspaper readers, and shortly to those of much of the world, her name was Nellie Bly.

For two years Nellie Bly had been a reporter for The World of New York, which under the leadership of its publisher, Joseph Pulitzer, had become the largest and most influential newspaper of its time. No female reporter before her had ever seemed quite so audacious, so willing to risk personal safety in pursuit of a story. In her first exposé for The World, Bly had gone undercover (using the name “Nellie Brown,” a pseudonym to cloak another pseudonym), feigning insanity so that she might report firsthand on the mistreatment of the female patients of the Blackwell’s Island Insane Asylum. Bly worked for pennies alongside other young women in a paper box factory, applied for employment as a servant, and sought treatment in a medical dispensary for the poor, where she narrowly escaped having her tonsils removed. Nearly every week the second section of the Sunday World brought the paper’s readers a new adventure. Bly trained with the boxing champion John L. Sullivan; she performed, with cheerfulness but not much success, as a chorus girl at the Academy of Music (forgetting the cue to exit, she momentarily found herself all alone onstage). She visited with a remarkable deaf, dumb, and blind nine year-old girl in Boston by the name of Helen Keller. Once, to expose the workings of New York’s white slave trade, she even bought a baby. Her articles were by turns lighthearted and scolding and indignant, some meant to edify and some merely to entertain, but all were shot through with Bly’s unmistakable passion for a good story and her uncanny ability to capture the public’s imagination, the sheer force of her personality demanding that attention be paid to the plight of the unfortunate, and, not incidentally, to herself.

Now, on the morning of November 14, 1889, she was undertaking the most sensational adventure of all: an attempt to set the record for the fastest trip around the world. Sixteen years earlier, in his popular novel, Jules Verne had imagined that such a trip could be accomplished in eighty days; Nellie Bly hoped to do it in seventy-five.